In the fall of my junior year at MIT (2019), I took 2.74, or Bio-Inspired Robotics. It was a very interesting course.

It taught me about impedance control, about how to practically mimic spring-mass-damper like behavior out of, say, a two-motor driven appendage. You could create, depending on what use case you wanted, behavior to mimic those k-m-b values, using this impedance control.

We also learned a lot about the various ways you could mimic legs, how different gaits work in two versus four legged animals, and how one might go about recreating that type of behavior in a legged robot.

In the second half of the course, we had group projects, where the goal was: find a question you want to answer, design an experiment to answer that question, and build out the hardware and perform the work needed to get the answer.

My group ended up creating a robotic jumping leg that we've affectionately come to know as Telescoping Timmy.

The question that we wanted to answer was: what is the optimal ratio of leg section lengths (thigh versus calf), and how does the power distribution between those muscles play into the maximum jumping height?

The physical apparatus was relatively simple, though tolerance issues and keeping an easy way to connect electronics are both topics that should never be forgotten, as we learned the hard way.

Glamour shot, because why not?

We had a six-foot telescoping boom extended out from a definitely-not-janky wooden frame (hey, at least it had plenty of bracing). This boom allowed the robotic leg to feel whatever amount of weight we desire; a counterweight whose appearance conspicuously coincided with the temporary disappearance of one of the dorm weight room's weights allowed this. The leg itself was comprised of the two motors themselves at the actual physical positions of the hip and knee joints, connected to adapters and joined by telescoping linkages that would screw together into one of four possible leg section lengths between fully collapsed and fully extended.

The setup itself, with its artisanal wooden base frame.

The boom additionally constrained the leg roughly to the vertical axis; we didn't really care about how far it could jump (we originally were interested in that question as well as height, but decided to reduce our scope when we realized how difficult it would be to get one axis working for testing).

To test the distribution of torque contributed by different muscles in the legs, we implemented that in the K64F FRDM boards (think fancy Arduinos with Arm processors that you can program through mbed). The amount of current allowed into each motor allowed an approximation of the amount of power contributed by each leg muscle.

The controller we used to drive this system was a hybrid position-torque controller; the position control came first to "crouch" the leg, and the torque controller generated an optimal torque trajectory for each muscle group over the course of the jump.

{{< videolocal src="/jumpingleg/jump.mp4" type="mp4" width="600" height="1200" >}}

An amusing video of our robot learning to jump.

After much tweaking of parameters and frustration with various electromechanical issues, we finally began to produce consistent jumps, and were able to take data to see if there was a trend -- and there was!

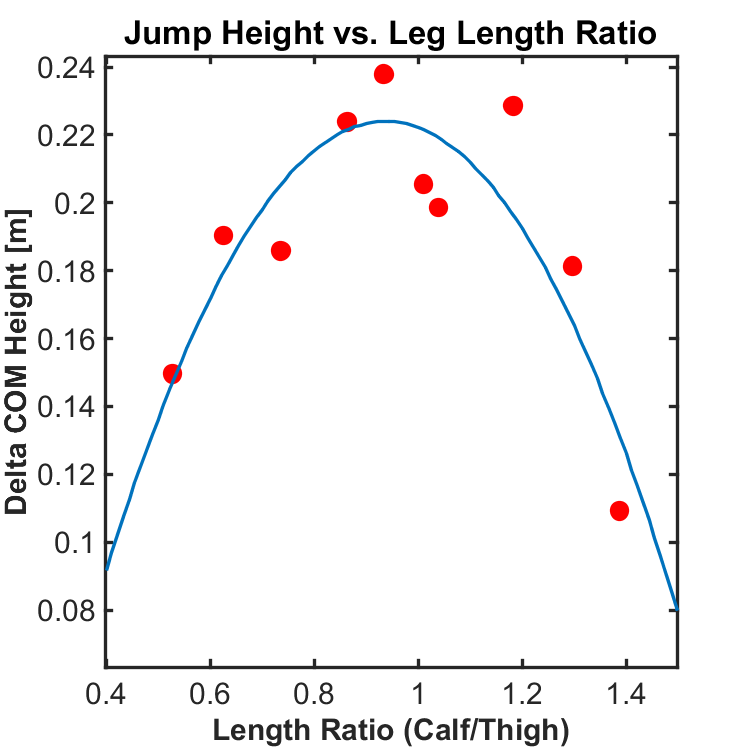

Plot of maximal jump height vs leg length ratio.

We ended up finding that the proportion of thigh length tended to increase your overall maximum jump height; that the leg ratio extremities drastically reduced performance; that there was no clear trend in knee or thigh muscle group power dominance; and finally, that the hypothetical optimal leg ratio was with a thigh that was 57% of your overall leg length, with the calf being 43%. However, you will note that the data is of course noisy; the only surefire conclusion we can draw from this is that near-equivalent (an 0.8-1.2 ratio range) leg lengths will tend to produce higher jumps for a given torque distribution.

Of course, no project would be complete without its own special set of implementation challenges. In our case, we spent a very long time working on the MATLAB simulations to try to get our virtual leg to, for lack of better words, stop doing acrobatics!

Check out our final poster here (PDF), which has a bunch of additional data and analysis!