In the Spring of 02020 at MIT, I took 2.782, or Design of Medical Devices and Implants.

Sounds about like what I'd be into.

It was an excellent class that maintained quality through the generally rough transition to online learning due to the Great Kick Out of March 2020 with the rise of the coronavirus.

For the second half of the term, we had to do a group project; my team ended up designing a novel formulation for a pericardial adhesion barrier, which we named Perigel.

In order to explain what Perigel is, I must first briefly cover the anatomical context and the clinical problem that we sought to address.

-The pericardium is a double-walled, fluid-filled sac that surrounds the myocardial wall -- your heart's muscle layer. -It fulfills a protective and lubricating role for the heart. It provides a first line of defense for the heart from lung infections. Additionally, it helps keep your heart in place in the body. -It has two major regions: the outer fibrous region, and the inner serous region (which is itself divided into the parietal and visceral regions, and contains the pericardial fluid that is essential to maintaining heart lubrication). -The face of the inner pericardium is coated in a mesothelial cell layer ("PMCs"), providing a slick barrier between the fibrous inside of the pericardium and the fluid filled region.

One thing that can go wrong with the pericardium is when a patient undergoes a heart surgery (coronary bypass, for instance).

When open-heart surgeries such as coronary bypass are performed, and the pericardium is damaged / sliced into in order to access the heart within for the necessary surgery, the result is that the patient must heal their pericardium in addition to everything else after their thoracic cavity is resealed.

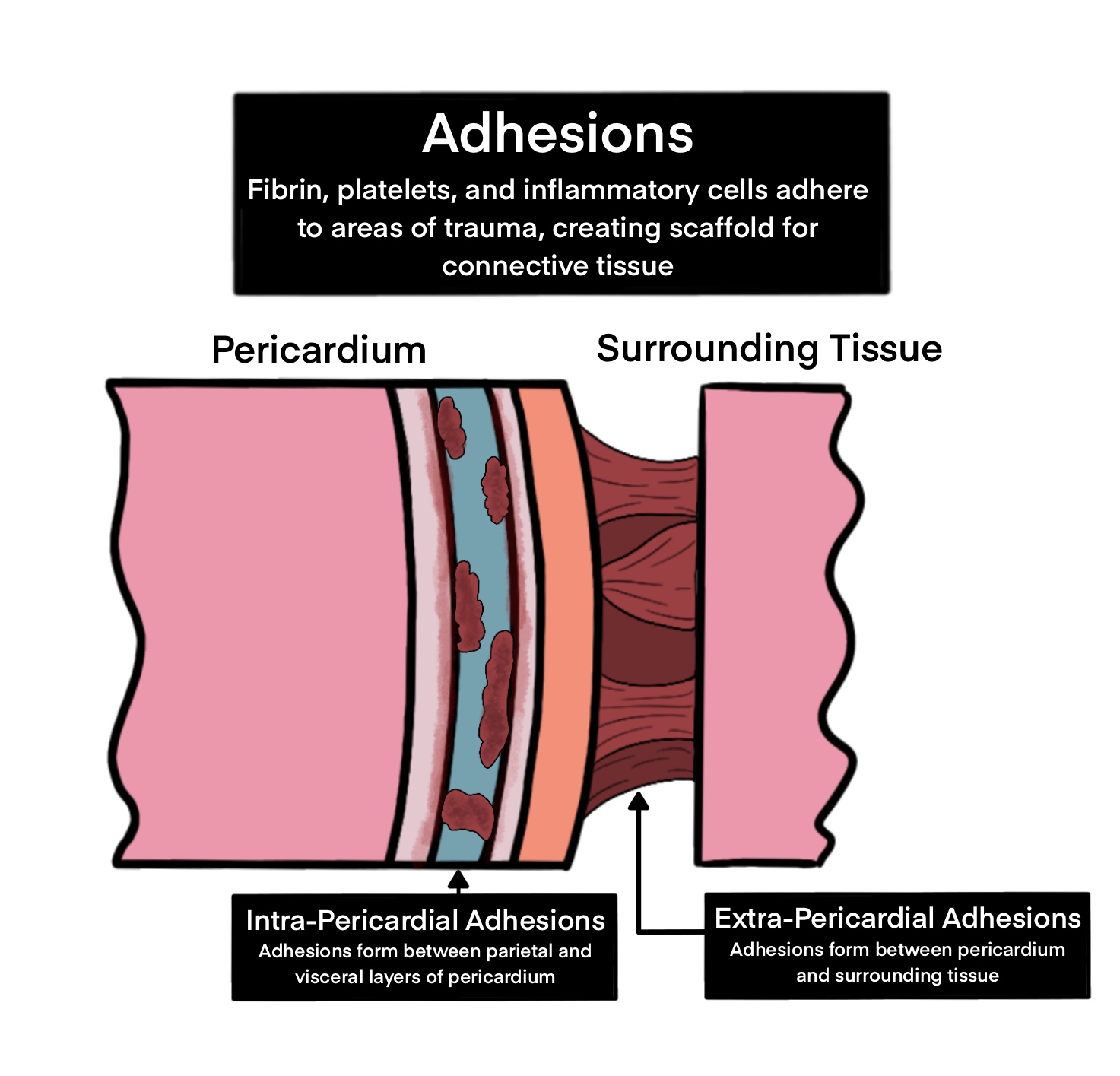

The conditions created by the surgical procedure are ripe for the proliferation of fibrous outgrowth. First, the PMCs wall is punctured: this sends PMCs flying into the pericardial fluid, and killing others. The fibrous surface inside of the PMC layer is thus exposed. Additionally, as there is an ample blood supply rushing in toward the wound (we are next to the heart after all!), one will see a buildup of platelets and fibrin. The body sends inflammatory cells which will seek to repair the damage with, you guessed it, fibrous scar tissue!

On the chemical side of things: the loss of the PMCs at the damaged site will inhibit the expression of glycoprotein-4 (PRG4), an inflammatory inhibitor against myofibroblasts, the common type one would witness acting in this pathology. Additionally, in the process of the surgical incision, cyclooxygenase enzyme 2 (COX-2) is activated, enabling the production of prostaglandins that signal for increased inflammatory response from the myofibroblasts.

Depiction of adhesion formation.

As you can see, the case of surgical incision into the pericardium truly does create the perfect storm for the creation of fibrous growth. The fibrous outgrowths from the pericardial damage site can spread outward, attaching to the thoracic cavity / chest wall, as well as inward to the myocardial surface.

The proliferation of these adhesions often creates the need for secondary surgeries in postoperative recovery to remove the adhesions a few weeks after the initial procedure. Symptoms of adhesion formation can include difficulty breathing and chest pain. The secondary adhesion-removing surgeries can themselves cause issues, as removing the adhesions is a delicate procedure that can risk catastrophic damage to the lungs and heart, as well as generally more time spent in operation.

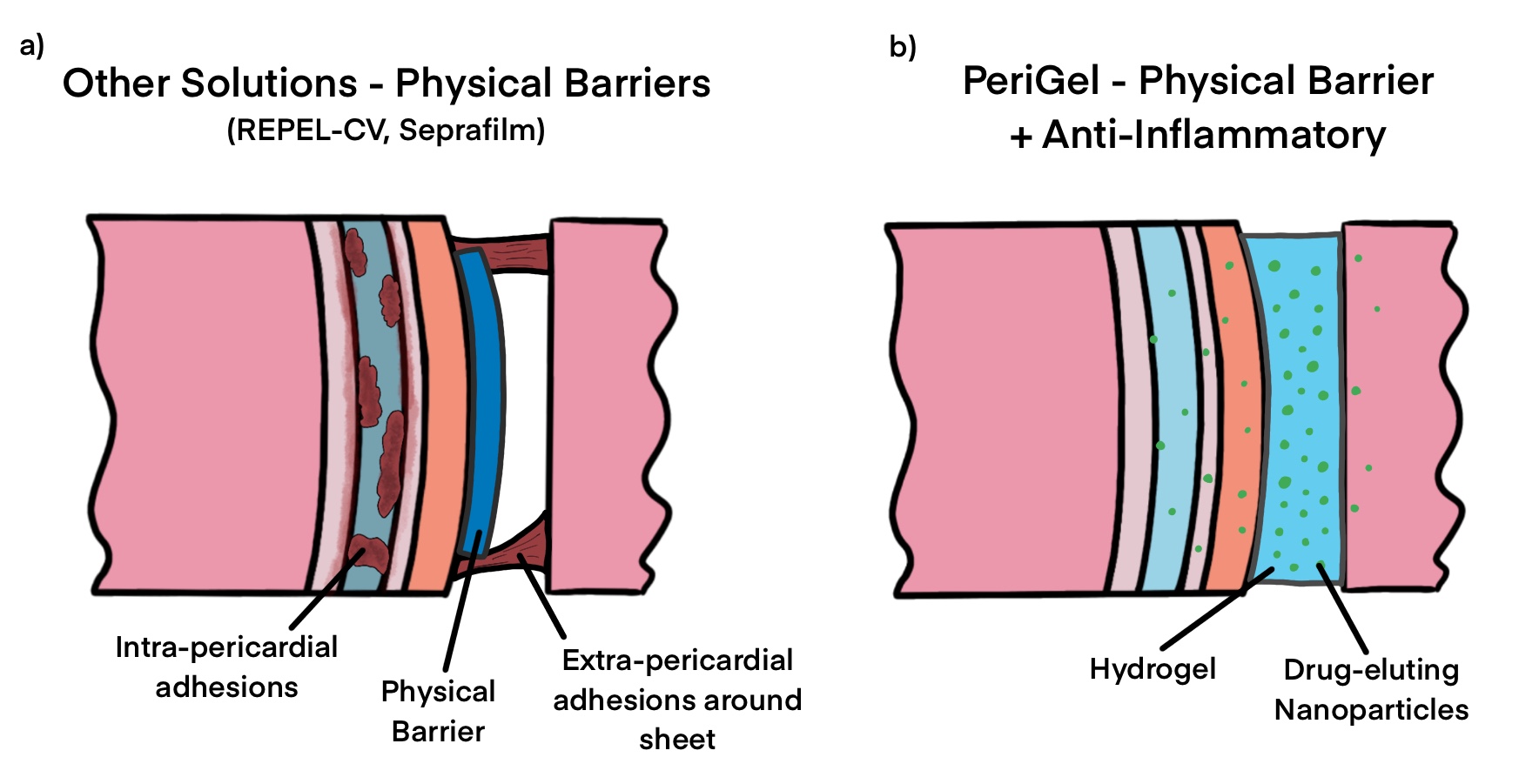

Prior adhesion barriers have often not targeted the unique anatomy of the pericardium, instead being repurposed from their original use cases in the abdomen or pelvic regions. Additionally, most prior treatments have only attempted to serve as a physical barrier to prevent adhesions, which unfortunately do little to prevent internal adhesions.

Our solution: barrier combined with inhibitor.

Enter the concept for Perigel. Our thought was, in essence: what if we could design something that served as both a physical barrier and as a chemical inhibitor of the inflammatory response? Long story short, we ended up deciding on a bioresorbable spray-on hydrogel that contains drug-eluting nanoparticles with small pellets of indomethacin, a primarily COX-2 inhibiting NSAID. Rather than risk damaging the entire body's ability to heal wounds globally by ingesting an NSAID, we sought to include small doses of the NSAID to be released over the course of a few weeks as the physical barrier is dissolved and absorbed by the body, inhibiting the fibrous growths over several weeks!

If this concept were to work, it could significantly improve patient outcomes, prevent excssive surgeries, and lower overall healthcare costs while improving quality of life and care.

Read the final project report here, which contains citations and significant elaboration.

Necessary disclaimer: I am not a doctor. None of this should be construed as medical advice. Obviously if this project were to be taken to proper clinical trials and the market, it would need significant further development. All images were created by my class teammate Dani and were pulled from our project report.