My senior capstone unfortunately coincided with the fully virtualized semester of Fall 2020. Nevertheless, I was able to have a meaningful team-based project experience working on an oxygen generation system and distribution concept in MIT's 2.75 capstone, Medical Device Design.

The course covered many relevant topics to medical device engineering; medical applications frequently require more than the typical mechanical engineer's set of tools -- you often need to incorporate electronic components to enable patients and practitioners alike to use your device. You also need to invest a lot of time and energy into talking to stakeholders: you need to understand who's going to use this, and how?

The project that I ended up working on was the ward-level oxygen generator for low-resource environments. I figured that it would be a solid engineering challenge whose outcome had a clear and demonstrated need in the form of a device specification supplying medical-grade oxygen-enriched air to patients in need of high-flow respiratory therapy. In this case, high flow was taken to mean an upper limit of 60 liters per minute (LPM).

Additionally, our team sought to minimize the requirement of specialized components in the development of our final specification, as well as in the benchtop prototype. Of course, certain specialized parts were used for ease in prototyping (e.g. 80/20 provides a means of rapidly deploying and modifying a machine configuration, but there is no particular reason 80/20 would be needed in the final product; once the specifications are set, simple aluminum bar stock could be used instead.) Simplified construction methods and easy maintenance were critical functional requirements for our project; as one of our clinical mentors and project sponsors was a doctor in a large hospital in Uganda.

By keeping in mind the constraints of working in a lower-resource environment, where consistent electricity supply and expensive manufacturing techniques were not a given, we hope to be able to avoid the fate that many generously but naively donated oxygen generation systems would meet: that of what I'm going to call the Fancy Tech Graveyard. When these expensive proprietary systems failed, nobody knew how to service them, and even if they did, getting replacement parts is frequently no easy task.

We decided after an initial literature review that the preferred method for generating oxygen given our constraints was that of pressure swing adsorption (we decided against electrolysis due to the high power requirement; in order to make them comparatively economical, we would have to recapture some waste energy through a hydrogen fuel cell, which is not exactly easily serviceable in the conditions we targeted).

The essential mechanism of PSA lies in the active material, often a zeolite (in our initial case, Zeolite 13X). When pressurized, the active material is capable of adsorbing nitrogen out of the atmosphere. Thus, our oxygen generation system is really more of an oxygen purification system. We used models of nitrogen adsorptivity from prior literature, and used MATLAB models to determine an ideal operating point of pressure and quantity of adsorbant material to maximize the purity of air exiting the system. In order to go beyond a first-estimate model, however, we would need to do some actual testing.

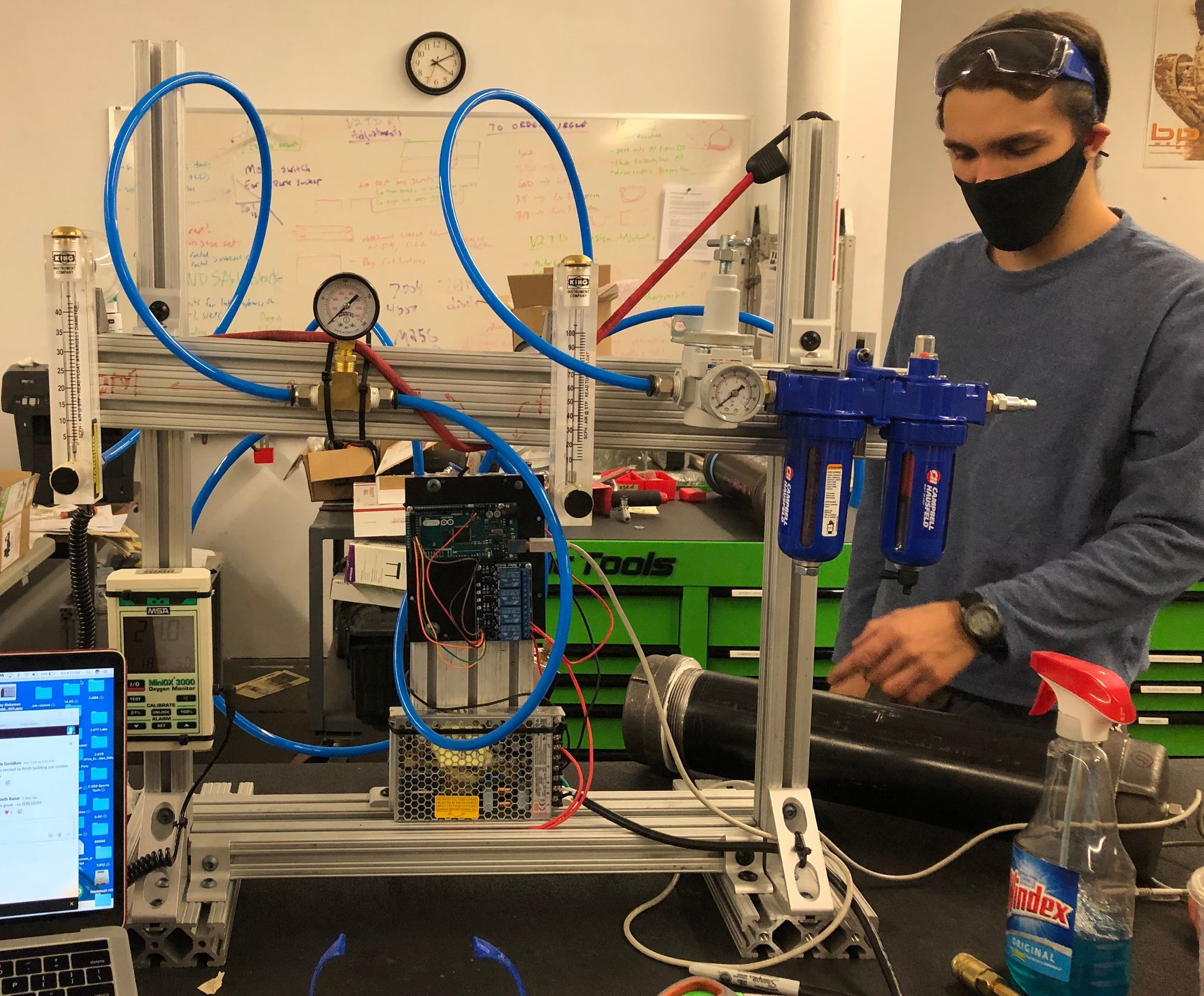

Me with the frame, early prototype tubing, control board and relays, and most sensors (and filter-dryer). Photo cropped of others for privacy. Mask, because covid. Hopefully by the time you are reading this, we won't need these anymore.

In order to reduce the size and cost requirements for our system architecture, the overall concept requires the use of pulsed-dose delivery (only delivering oxygen on inhale); given estimated breathing patterns of COVID-19 hospitalized patients, we determined that by using pulsed-dose delivery, we could achieve a 4x multiplier in therapeutic equivalent for oxygen delivery. In other words: by pulsing delivery, we could get away with a generator that continuously produced a time-averaged rate of 15 LPM (at standard temperature and pressure) instead of the continuous 60 LPM that we had originally set as our target.

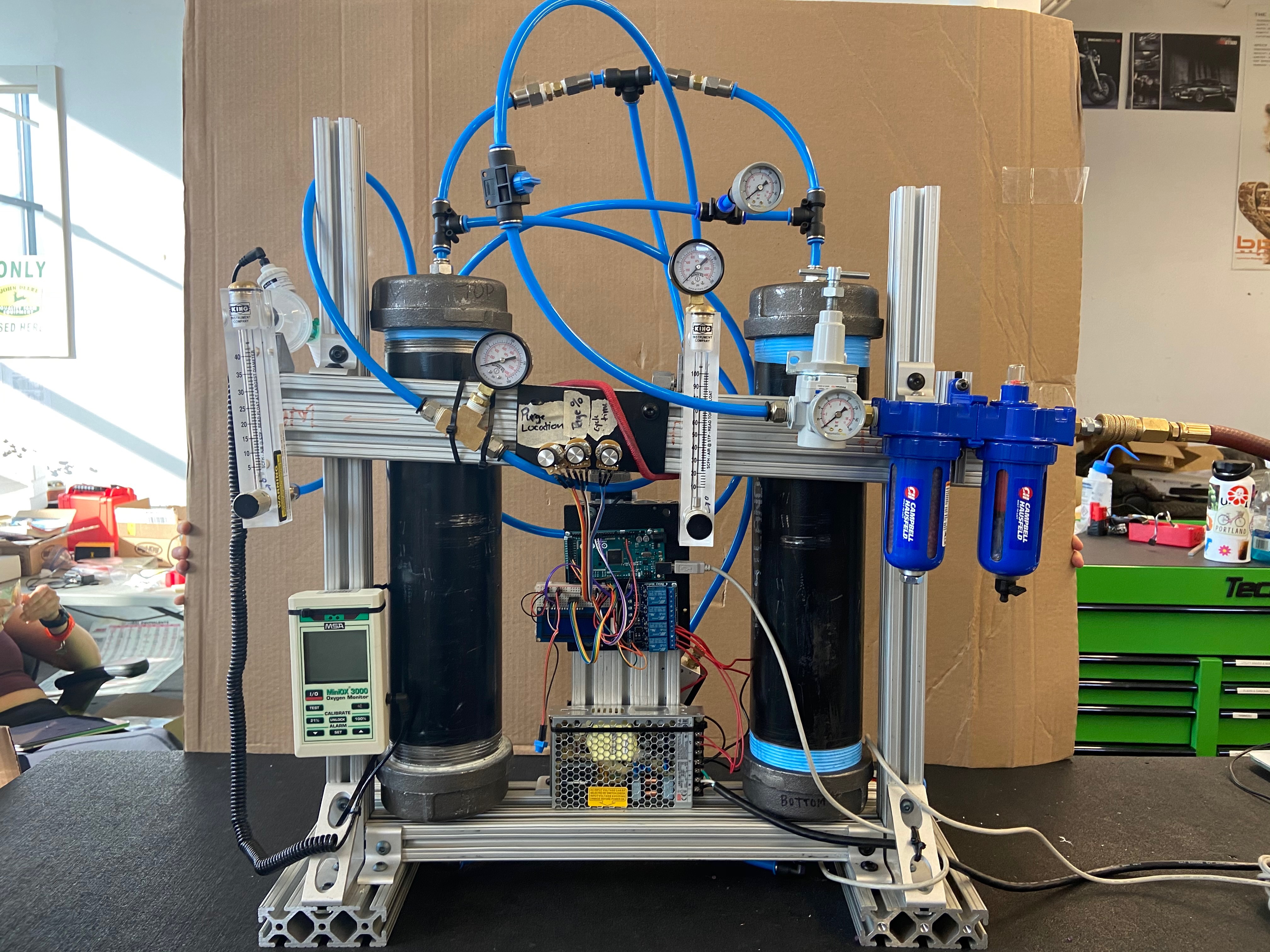

We selected to a certain quantity of zeolite in either of two iron cylindrical adsorption chambers. Initial testing showed that we were getting best results for a given pressure with certain cycle times. At every cycle switchover, an Arduino microcontroller program would trigger relays and switch several solenoid valves, redirecting the now-saturated chamber's air to atmosphere (thus depressurizing it and purging the zeolites of nitrogen), while the alternate chamber begins to fill and pass oxygen-enriched air on to the output.

We tested a variety of pressure points (controlled via a pressure regulator placed after a filter-dryer that removes excess moisture from incoming air) and a ball flowmeter at the output allowed us to restrict the flow to various maxima (assuming that there would be -- and there was, in the data -- a tradeoff between quality and quantity of oxygen-enriched air).

The final prototype as of December 2020. Minor improvements followed in early 2021 (better zeolite, re-sealed chambers, less janky valves).

The final version of the prototype for the class was capable of producing substantially oxygenated air, though this fell short of our initial goal of 15 LPM at >=90% oxygen. However, we did demonstrate that the system architecture we created is capable of creating an output that is in fact, at these flow rates and percentages, already therapeutically applicable (especially in infant wards).

Note: I've intentionally left a lot of specific figures, results, and configuration details vague in this, as our work is (hopefully) going to be published. Once I am able to, I will update this article with additional details and our final report.

Last updated 2021-03-09